How to Finally Make Something

…or how we put off our creative dreams for our entire lives

Growing up in the early 2000’s, I spent a lot of time participating in online creative communities. This experience planted a question in my head— a question that would come to define a big portion of my life:

“Why do 99% of people struggle to get past the first mile in their creative projects? How could I join the 1% that actually make things?”

After a decade of introspection, creative attempts and reading, I found an answer that worked for me. Overcoming the barrier to freeform creation has felt like one of the best things that’s happened in my life.

If you’re a creative yearner like I was, I hope this insight will help you overcome the barrier too.

The Problem: Fantasy Games

Creativity ultimately means stepping forward without knowing where we’re going. Unfortunately, unstructured and ambiguous tasks make us anxious.

To avoid this anxiety we constantly substitute playing the real game of creation with other activities that feel more structured — what I’ll call “fantasy games”.

Most of the time we do this subconsciously, without even recognizing it. Many of us have been doing this for almost our entire lives, and will continue to do so until death (unless we intervene).

Making something original simply requires avoiding playing these fantasy games too often, in order to play the real, scary game of creation. That probably either sounds too simple, or too ambiguous — but let me elaborate below.

I’ll nickname four ways this ailment shows up as:

Learning Syndrome

Tool Syndrome

Process Syndrome

Maintenance Syndrome

1. Learning Syndrome

A programmer piling up technical books and not programming. A music producer completing online courses but not producing. A game developer completing tutorials but never making their own games.

The learner substitutes their creative pursuit with: “Just another book and I’ll finally be able to get started.” But that day never comes. Knowledge fades, becomes less relevant, and you can never know everything. But learning feels good. There is no apparent risk to reading a book: finishing it and putting it back on the shelf will always provide us with a dopamine reward.

The easiest cure for Learning Syndrome is to adopt an attitude of just-in-time learning: start your project, using any step you can conceivably make, and then only learn whatever you need to take step number two.

Of course, there is a definite place for long-form learning, but when in a creative mindset we need to err on the side of just-in-time learning if we are to avoid getting constantly sucked into this trap.

2. Tool Syndrome

As a music producer I accumulated a lot of hardware synthesizers, drum machines and gadgets. Some of my friends collected guitar pedals and other gear. Photographers accumulate cameras, lenses and other paraphernalia. Programmers spend a lifetime collecting development tools and configuring environments.

For me the feeling often was: “If only I had an MS-20, then I could sound like artist X and make good music!” I’d get a piece of equipment, enjoy the dopamine, have a great spurt of creative confidence, and then… “If only I had a Tempest”.

The solution to this plight? Find your set of tools and stick to them. Anything available today is probably 10x better than what your favourite creative was using 10 years ago. The yearning for new tools is very often an excuse to avoid the ambiguity of moving your project forward.

3. Process Syndrome

Process Syndrome is closely linked to Learning Syndrome. Processors believe they just need to learn the right method and follow it to realize their creative dream. This often results in “going through the motions” of creation without ever entering a state of deep creative flow or producing something original.

Processes replace the ambiguous creative tasks that we’re afraid of with a dopamine-rewarding prescription that feels like it’s sure to work.

We eat up general processes on how to do things (The Pomodoro Technique, Zen Habits, Getting Things Done), on how to live life (fad diets, fad exercise plans, regimented mediation routines, new years resolutions) and of course, on how to do our craft.

I once attended an event where filmmaking students were showing their work. They excitedly shared with each-other what kind of camera and lenses they used and what eclectic technique they used to process the film. It’s almost like their primary concern was not making art, but gaining the approval of their peers.

“Aha!” I thought. “This is exactly what is happening in my musical circles and I’m partaking in it”. Doing things a certain way and using certain pieces of equipment really did generate nods of approval from other musicians.

But no one except our creative peers cares how we accomplish our work. The idea that we can create good output by doing things The Right Way or The Cool Way is a lie, and this lie shifts our focus far away from the real, ambiguous task of trying to create something good.

Since the sausage factory of software development is so open and team-oriented, software developers are possibly more effected by this bias than anyone. Developers fight over the right way to format code, and try to implement the Right Processes the Right Way (test-driven development, pair programming, Scrum). Left to their own devices, programmers will re-write their code twenty times in a quest to Do Things Right.

But in all domains, we never find The Right Way, it’s just a mirage.

Does that mean we should never try? No, not at all. Some processes and standards are quite valuable. But we need to remind ourselves constantly: At the end of the day, it is not about the process, it’s about the output. There are absolutely no points for doing the process “right”, it is only a tool to use towards output.

4. Maintenance Syndrome

Constantly cleaning up, organizing files on our hard drive, running errands, putting out little fires and making inconsequential project todo lists: these are all symptoms of Maintenance Syndrome.

Maintenance tasks in our life and in our projects are usually very clear-cut. They seductively offer a clear problem and a clear solution. The structure-seeking part of or brain loves this and will endlessly procrastinate important ambiguous tasks in favour of taking these on.

When we are pulled into this game we usually think: “let me just check all these things off my list first, then I’ll do the hard thing”. There’s one big problem with that: there’s absolutely no end to these kinds of minor tasks in life. They will grow to take as much space as we have to offer — completely crowding out creation.

Many Others

These are just four examples of how we replace our scary and ambiguous quest of creation with structured fantasy games, but there really is no end to the number of ways we can be pulled off the creative path. Our temptations are unique to ourselves.

The intention is not to frame these activities as bad. They’re certainly not. But we need to be vigilant about them, and deeply understand our reasons for doing them — in order to make sure they are not crowding out creation from our life.

Mitigation

Whew. So, We’ve covered four “fantasy games” that we use to endlessly distract ourselves from actually achieving creative output. But what does the real game of creativity look like? I see it as two sub-games, which I’ll call the “tactical game” and the “long game”.

1. The Tactical Game

The tactical game is what happens when you sit down to actually do your craft. This largely involves discovering a state of flow, where you are not thinking too much about your actions and feeling a natural enjoyment as you progress. The main way I’ve found to achieve flow is to work on something I naturally enjoy, to force past the hurdle of getting started and to create interruption-free time/space.

But wait! This prescription is starting to sound a bit like Process Syndrome. Even the quest to find flow can just become another distracting fantasy game.

These are little things that work for me, but I don’t take them too seriously. If a moment of inspiration strikes and I have not completed my ritual, I just let it take me. That’s the most important part.

2. The Long Game

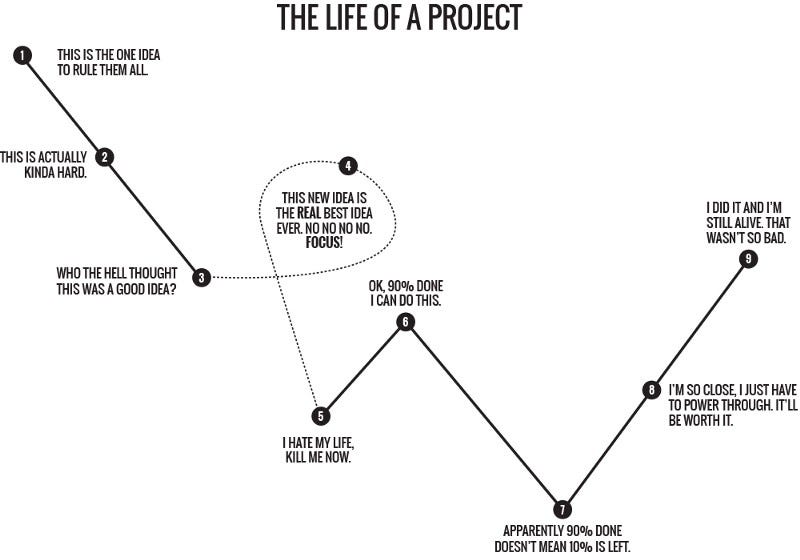

The hardest part is learning to emotionally navigate the life of a creative project from start to finish. It can take a lot of practice to really master this.

Knowing when to give up completely, when to press on, when to perfect and when to let flaws go, is an intuitive skill. This skill can’t be learned by proxy through any of the fantasy games above, it is only learned by actually attempting to go through the process with real projects.

And that’s why it is so, so critically important to be wary of the fantasy games: every day you spend completely absorbed in the fantasy games, is another day you could have used in learning how to ride the real rollercoaster better.

Final Thoughts

I’m still no expert at this, and am working everyday to improve my output. But I’d be ecstatic to report to my younger self that I did finally find a way make some things, finish music and write this blog post. These accomplishments bring me the deepest kind of satisfaction.

And now after having found a way to play the real game, I know that no matter what circumstances life throws at me and no matter what tools I have available, I will always be able to find creative joy.

I’d like to send a heartfelt “thanks!” to Elling Lien/Unpossible for bringing RPM (a challenge to write and record an album of music in 1 month) to Newfoundland. It was during this challenge that I finished my first creative work and really began to feel understand what it was to ride the real creative roller coaster from start to finish.

If you have yet to complete a creative journey from start to finish, deadline-driven events like RPM, Startup Weekend, Global Game Jam and NaNoWriMo are an amazing place to start.

Scott is currently building legal technology at Rally

Twitter: @scottastevenson