Pattern Matching Beats Narrative Reasoning

Why good bets can't be easily explained in words.

Most of my losing bets, in both business and investing, were driven by narrative reasoning: short compelling stories about the world that sound smart.

“Marijuana is about to be legalized in Canada. This is a rare opportunity to invest at the ground floor of a new industry.”

“I’m going to invest in a cobalt mining company because they won a contract with Tesla.”

Before we launched Spellbook, we thought: “Let’s launch Shopify for Lawyers, because hourly billing lawyers care more about getting business than efficiency”

We love stories. Narratives are like a virus and a mind-altering drug. When they hit our ears we feel: “Ah! That makes sense”. They add clarity in an overwhelming world. And then we feel compelled to share the story with others. The clarity felt good and we want to share that feeling. More importantly, sharing the story makes us feel smart.

This contagiousness makes narrative reasoning extremely dangerous. Because simple stories often make horrible bets.

Multi-Causality

Concise stories don’t work well to drive action in the real world, because the real world is so multi-causal. There are hundreds, or even millions of factors that cause a bet to have a good outcome.

Imagine the best chess AI engine in the world: for any board state, it has to consider hundreds moves, and then a huge number of branching futures. Great chess engines can’t simply use narrative reasoning like: “a good offense is the best defense” to win. These engines are more like spreadsheets: massive matrices of numbers and probabilities. They can make moves that are impossible for us to comprehend using language-based reasoning.

The worst part? Real life is way more complex than chess.

From this we can conclude that the most optimal way of strategizing about the world is definitely not by using a short sequence of words.

Legibility Bias

Raw reality is not very legible. That is, it’s not simply structured and easily comprehensible by us. Although narratives make us comfortable, they’re not enough to capture the essence of reality. Reality is messy.

One of the most impactful things I’ve ever read is Venkatesh Rao’s “A Big Little Idea Called Legibility”. It talks about how we are drawn to orderly, legible systems—but how those systems often fail. We even tear up messy, working systems, replace them with nice orderly systems, and see the order fail terribly. We put too much value on legibility. Let’s call this legibility bias.

For instance, in the image below there is a legible “scientific forest” and an illegible organic forest. “Scientific forests” were a failure, even though their legible structure made us feel confident in the approach. Messy illegible forests remain successful.

Why does legibility bias persist across society, even when we are aware of it? One answer is: it soothes people. We are conditioned from kindergarten onwards to believe that there is a crisp, clear structure to the world. That there are crisp reasons why things happen. In the world of startups, that illusion is demolished if you stick at it long enough. But large organizations “cast the illusion” of legibility to soothe and create a sense of order among employees, while those in the inner circle of upper management face messy reality head-on.

Also in organizations, communication bandwidth means that you need crude, simple stories to get the ship headed in the right direction. Simple stories are a necessary evil in management. But big decisions at the top of an organization are not actually being made this way. Simple stories are a tool to motivate and direct people in approximately the right direction.

If someone has spent years at a large company, and has not been in the “inner circle” of management—it is easy to see how they might confuse the tool that is being used to motivate them with the process in which effective decisions are actually being made.

People misunderstand the utility of simple stories. They’re more of a management tool, a political tool, a motivation tool, and a marketing tool than a decision making tool.

Finding Alpha By Correcting Against Legibility Bias

Good bet making is about “finding alpha”. That is, betting on opportunities that others have underestimated. Since humans have a strong bias for legibility, highly legible bets get bandwagoned.

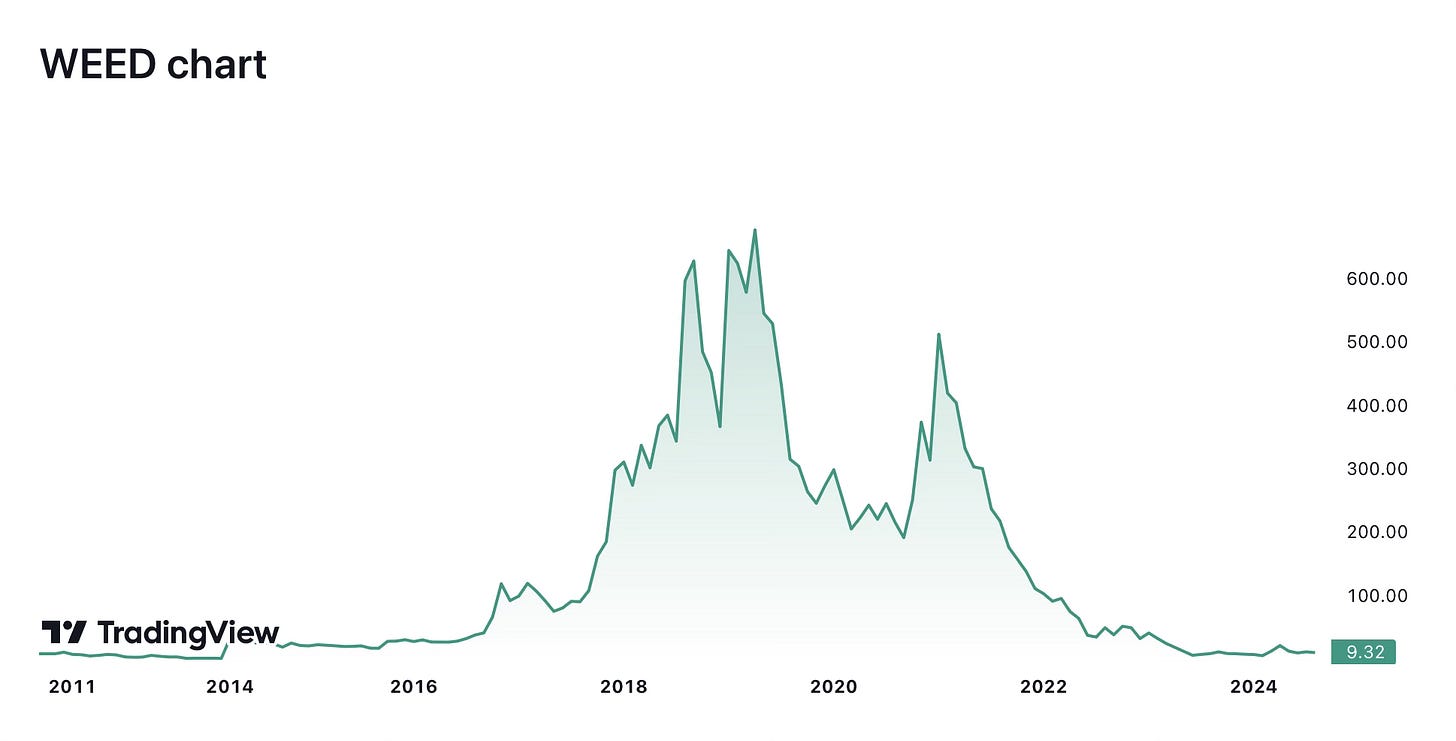

For example: “Since marijuana just got legalized in Canada, I’m going to buy $WEED stock to get in at the ground floor of a new industry”

Here’s how that worked out:

Even if these narratives are correct, they are too visible to markets and get quickly over-bought. In other words: The stock price gets too high before you make your bet. Or too many competitors get to the business idea before you. Or too many musicians make similar sounding songs. This reasoning works across any competitive domain.

A really good place to find bets that are underestimated is in the illegible.

Intuition

If stories don’t work, how do we survive at all in a world so complex and multi-causal? Well, simple stories can work for basic survival: “I need to eat to survive”.

But to find good bets that others don’t see, we need to leave crisp stories behind and think more like a chess engine. We need to digest raw hyper-dimensional reality. But how do we do that without putting our situation into a 100,000 x 100,000 spreadsheet?

The first answer is: intuition.

We already have 86 billion neurons in our brain that are doing something similar to a chess engine. We can’t see exactly how it works, but it can send us much more valuable signals about the world than narratives do. If we digest enough data, our brain starts pattern matching automatically. Pattern matching is how we position ourselves to throw a basketball and recognize our friends faces. Those are not things we think about in words.

Running fast using intuition to make decisions can be extraordinarily effective.

But what if our intuition is bad? What if our intuition differs from that of our team?

Manual Pattern Matching for Teams

That’s a lot of words to say: “trust your gut!”. But what if you haven’t developed intuition? Or what if your intuition disagrees with the intuition of your team?

There is a slightly more legible approach that I’ve found effective:

Look at your past bets and ask yourself: what are the 10-20 attributes that mattered? List them out, and then go through each of your winning and losing bets, noticing which attributes they had.

We did this for all the product feature bets we made at Spellbook, and were able to correlate 16 attributes with what made a successful product bet. And many were surprising.

Almost none of our correlated attributes had to do with the narrative of the feature itself. We discovered a bunch of other things that mattered:

Can a lawyer get value from the feature instantly with absolutely zero configuration?

Was someone on the team so inspired to build something that they “started without permission”?

Is the feature “whole” rather than a stepping stone to get somewhere else?

Can the feature be fully prototyped in 2 weeks?

We ended up with a framework that is a middle ground between legible, narrative based reasoning and intuition. And the best part is we could objectively score prospective bets in this framework.

It brings us a little closer to reasoning like a chess engine. These signals increased our hit rate significantly when we used to not hit at all.

For years we had been listening to the gospel: “talk to your customers! Build what they ask for!” This was helpful, but it had an catastrophic blindspot that was causing us to make losing bets for years.

We were missing an entire universe of patterns outside of the tunnel vision of stories.

Pattern Matching in Investing

This approach also helped dramatically improve my performance in investing.

When I started noodling in active investing almost 20 years ago, I relied on narrative “reasons” and news headlines to make bets. My active portfolio produced neutral returns for nearly 10 years (adjusted for inflation, that’s a big loss). Those narratives simply didn’t capture the thousands of factors that impacted stock price. And if they did: well everyone else was jumping on the same bandwagon and pushing up the buy price where the bet became too expensive to make sense.

Over the last 9 years I switched to a pattern matching approach. My active portfolio has performed ~20x better than my passive portfolio over that period.

To improve my ability to pattern match, I really like to “soak” in data. I read lots of charts and try to make written predictions on them regularly. I check back on how my predictions fared. Eventually making trades started to feel like throwing a basketball. My brain started to develop a deep intuition for technical and fundamental signals, and how they combine to make a “swish”.

Independent-Mindedness

Pattern matching is not hard. Our brains are wired to do it. The hard part is being independent-minded enough to believe your own conclusions.

To do that, you need to escape the universe of simple stories we are surrounded by. Stories are the threads that hold society together. We are fish and stories are our water. Repeating popular stories grants us head nods and social acceptance.

For example, “You can’t beat the market, dollar-cost average into index funds!” is the kind of viral story that will earn you nods of approval from millennials and upvotes on Reddit.

Pattern matching, on the other hand, can drive you to make moves like an advanced chess engine. Moves that others find alien and incomprehensible.

If your bets don’t generate some confused looks, they’re probably too obvious, and thus overdone.

“To believe that what is true for you in your private heart, is true for all men,—that is genius” —Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance

Excellent post! Do you use a Weekly Business Review-type process at your company? It seems like it's been very successful for amazon and i always thought about it as helping them develop a "true" story about what is going on in the business, but perhaps looking at hundreds of charts very quickly per week just helps people pattern match good and bad opportunities

Exceptional post; thanks for sharing. Came across this somewhere and could't find it again, but GPT helped me out!

It does seem like empiricism/the scientific method is the only way - you really have to find the ground truth yourself.